|

FUEL & ENERGY POVERTY

Please use our A-Z INDEX to navigate this site where page links may lead to other sites

|

|

POVERTY - A household is said to be in fuel poverty when its members cannot afford to keep adequately warm at a reasonable cost, given their income. The term is mainly used in the UK, Ireland and New Zealand, although discussions on fuel poverty are increasing across Europe, and the concept also applies everywhere in the world where poverty may be present.

What is fuel poverty? Fuel and energy poverty are linked. Fuel poverty normally applies to home heating, while energy poverty is broader, covering almost anything in the home that requires electricity or other fuel sources needed to sustain modern living.

While seeking to provide energy and fuel for life, we must be wary of global warming from the burning of fossil fuels. This means providing energy or fuel that is renewable and as close to zero carbon as possible. Otherwise, with the drive for electrification and cheap energy for all, we are engineering in warming of the planet - and that we must avoid - for the sake of planet earth and all life onboard.

The ideal is for all new homes to be well insulated and energy self-sufficient, including heat and electricity.

Utopia Tristar RE flatpack timber mobile home designed for the United Kingdom. This is a 20'x18' foot affordable starter home example with a 12 sq/m solar conservatory as part of the roof, which generates 12 kW during periods of intense sunshine. Thus if the sun shines for 6 good hours, you will capture 72kW/hrs of energy. 8 hours will yield 96 kW/hours and so on. Minus of course any losses in efficiency in conversion. If this mobile home were adapted to be a house, you would not see the pillars. Instead the pillars would be below ground level and could be mounted on a concrete raft, or footings. This design is flood resistant and can even be made to float for tsunami prone regions. All of this cost and customer preference dependent. Copyright © diagrams Climate Change Trust 2013. All rights reserved.

ENERGY POVERTY

Energy poverty is lack of access to modern energy services. It refers to the situation of large numbers of people in developing countries and some people in

developed countries whose well-being is negatively affected by very low consumption of energy, use of dirty or polluting fuels, and excessive time spent collecting fuel to meet basic needs. It is inversely related to access to modern energy services, although improving access is only one factor in efforts to reduce energy poverty. Energy poverty is distinct from fuel poverty, which focuses solely on the issue of affordability.

Energy tariff increases are often important for environmental and fiscal reasons – though they can at times increase levels of household poverty. A 2016 study assesses the expected poverty and distributional effects of an energy price reform – in the context of Armenia; it estimates that a large natural gas tariff increase of about 40% contributed to an estimated 8% of households to substitute natural gas mainly with wood as their source of heating - and it also pushed an estimated 2.8% of households into poverty - i.e. below the national poverty line. This study also outlines the methodological and statistical assumptions and constraints that arise in estimating causal effects of energy reforms on household poverty, and also discusses possible effects of such reforms on non-monetary human welfare that is more difficult to measure statistically.

Increasing energy consumption has long been tied directly to economic growth and improvement in human welfare. However it is unclear whether increasing energy consumption is a necessary precondition for economic growth, or vice versa. Although developed countries are now beginning to decouple their energy consumption from economic growth (through structural changes and increases in energy efficiency), there remains a strong direct relationship between energy consumption and economic development in developing countries.

INTERNATIONAL COOPERATION

EUROPEAN UNION

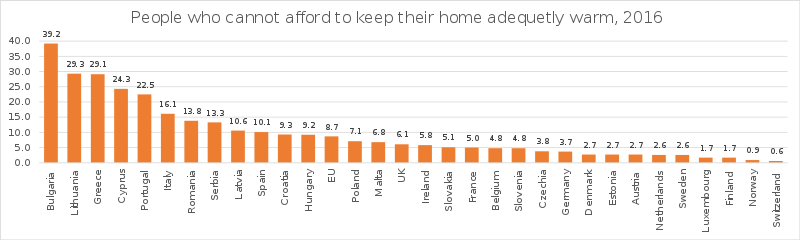

There is an increasing focus on energy poverty in the European Union, where in 2013 its European Economic and Social Committee formed an official opinion on the matter recommending European focus on energy poverty indicators, analysis of energy poverty, considering an energy solidarity fund, analyzing member states' energy policy in economic terms and a consumer energy information campaign. In 2016 it was reported internationally how several million people in Spain live in energy poverty, causing deaths and also anger at the electricity suppliers' artificial and "absurd pricing structure" to increase their profits.

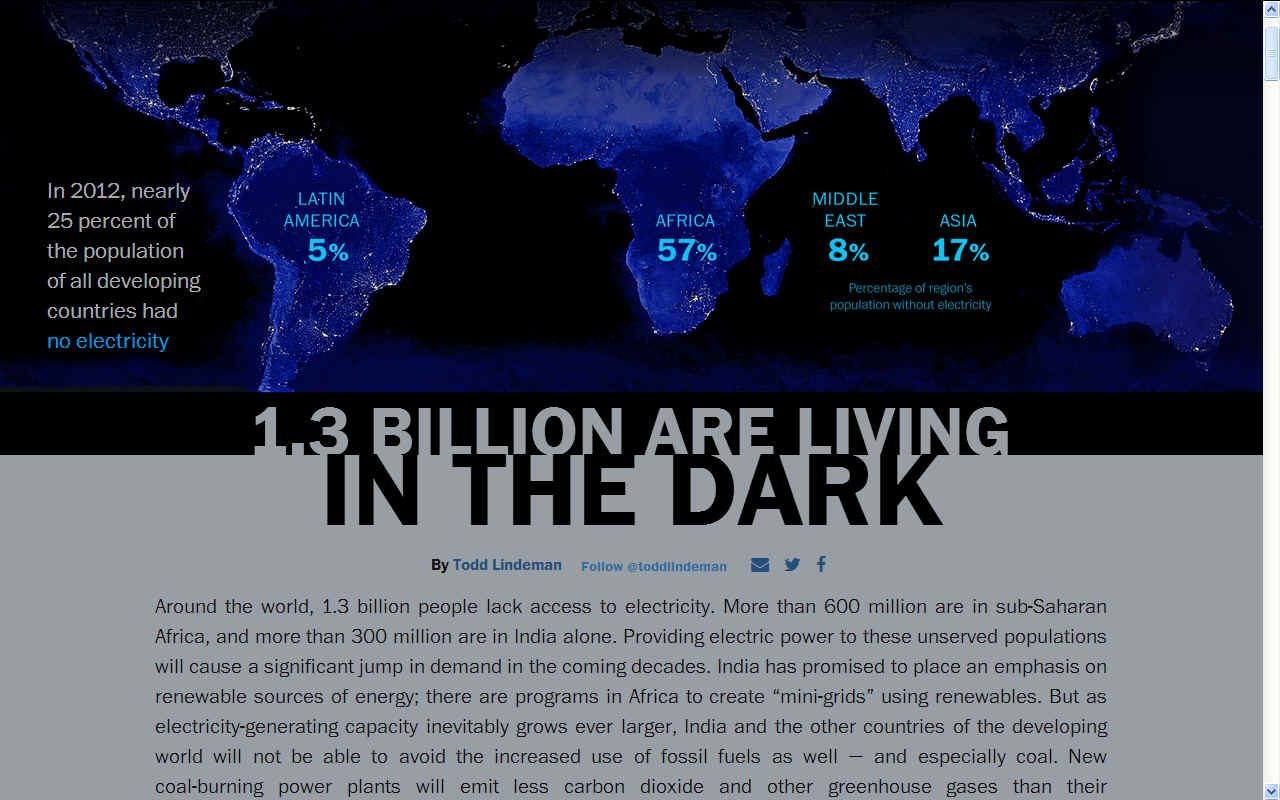

Energy poverty mostly affects low-income economies and rural areas; electrification is making progress, but clean-fuel development is stagnating. From 2000 to 2016, the number of people without access to electricity dropped by nearly 35 percent, from 1.7 billion to 1.1 billion. During that period, about 1.1 billion people gained access to electricity, exceeding global population growth of 0.6 billion people. India experienced some of the world’s fastest rates of electrification, with an average of more than 33 million people gaining access every year.

By contrast, access to clean cooking fuels did not make significant progress. Over the past two decades, the number of people without fuels for clean cooking remained stagnant at 2.8 billion. Globally, access to non-solid fuel is a more acute problem than access to electricity; in almost every country, the transition to electricity has been faster than to clean cooking fuels.

The International Energy Agency says deploying energy for all would have a very limited impact on energy demand (more than 37 MTOE in 2030) and a small positive impact on climate change (an increase of 70 MT of CO2 emissions by 2030, but an overall reduction of greenhouse gases of 165 MT CO2 equivalent in the same period).

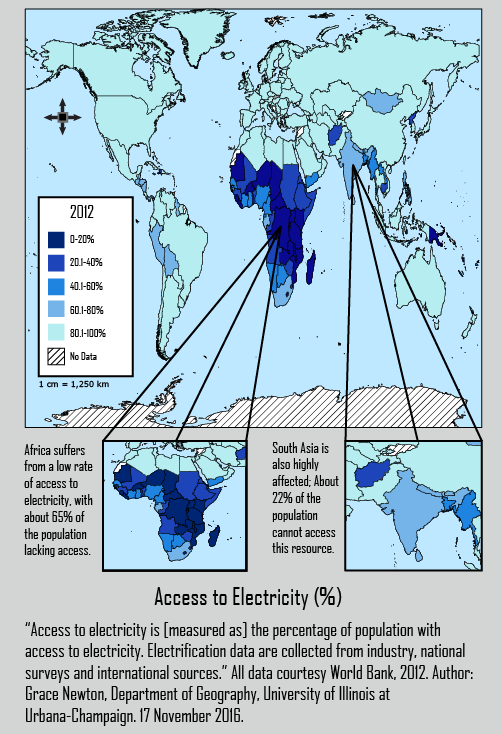

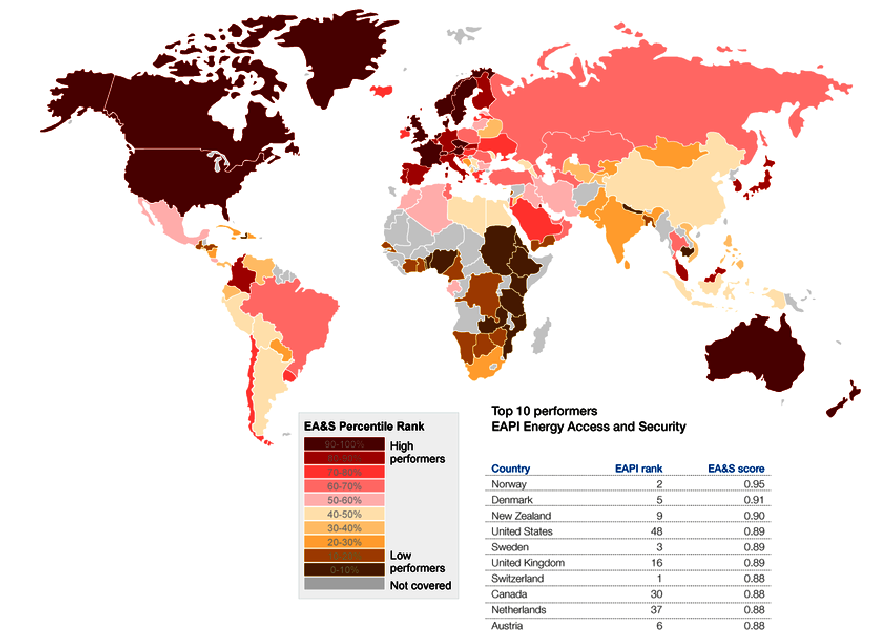

The 15 worst-affected nations in terms of the proportion of the population experiencing energy poverty are all in Africa. In these countries, the share of the population living with no access to electricity ranges from 65 to 92 percent, while 95 to 98 percent of people lack access to clean fuels for cooking. But the largest populations suffering from energy poverty are in India and China. In 2016, 239 million people in India did not have access to electricity (accounting for 22 percent of the global population without electricity access). Combined, India and China accounted for 1.3 billion people without access to clean fuel (48 percent of the global population that lacks clean fuel access).

In general, access to electricity and clean fuel varies according to a country’s average economic wealth. In low-income countries, the percentage of the population with access to electricity ranges from 10 to 40 percent, compared with 40 to 80 percent in lower middle-income countries. Only 5 to 30 percent of people in low-income countries have access to clean fuels, compared with 30 to 50 percent in lower middle-income countries.

Given existing policies and investments ($334 billion), the International Energy Agency expects a global reduction in the number of people who lack access to electricity from 1.1 billion in 2016 to 0.7 billion in 2030. Between 2030 and 2040, the reduction will weaken unless further measures are taken. The outlook for access to non-solid fuels is even worse. The global population lacking access to modern fuel is only expected to fall by 7 percent between 2016 (2.8 billion people) and 2030 (2.6 billion people). Investments would need to quadruple globally to provide universal access to clean fuel, with about 30 percent of spending allocated to Africa.

GLOBAL ENVIRONMENTAL FACILITY

"In 1991, the Work Bank Group, international financial institution that provides loans to developing countries for capital programs, established the Global Environmental Facility (GEF) to address global environmental issues in partnership with international institutions, private sector, etc., especially by providing funds to developing countries’ all kinds of projects.

The GEF provides grants to developing countries and countries with economies in transition for projects related to biodiversity, climate change, international waters, land degradation, the ozone layer, and persistent organic pollutants. These projects benefit the global environment, linking local, national, and global environmental challenges and promoting sustainable livelihoods. GEF has allocated $10 billion, supplemented by more than $47 billion in co-financing, for more than 2,800 projects in more than 168 developing countries and countries with economies in transition.

Through its Small Grants Programme (SGP), the GEF has also made more than 13,000 small grants directly to civil society and community-based organizations, totaling $634 million. The GEF partnership includes 10 agencies: the UN Development Programme; the UN Environment Programme; the World Bank; the UN Food and Agriculture Organization; the UN Industrial Development Organization; the African Development Bank; the Asian Development Bank; the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development; the Inter-American Development Bank; and the International Fund for Agricultural Development. The Scientific and Technical Advisory Panel provides technical and scientific advice on the GEF’s policies and projects."

ETHIOPIA - In a country of approximately 100 million people, roughly 44% of Ethiopians have access to electricity. Ethiopia’s National Electrification Program 2.0 aims to fill this electricity access gap: by ensuring 100% access by 2025.

FUEL

POVERTY IN ENGLAND & WALES

Key fuel poverty factors

Number of households in fuel poverty is rising

AFRICA & INDIA - In 2015 a world report concluded that 1.3 billion people were living in the dark. Rather than looking at this as a problem, we might take the alternative view that this is an opportunity to build a sustainable off-grid supply network using only renewables - so ensuring that what might be perceived as more strain in terms of climate change, might be prevented. We might achieve this with mobile units to begin with, until the affected regions have time to build permanent networks with installed wind and solar energy generators.

You might argue that they are the lucky ones. If they do not get on the development merry-go-round, they have nothing to lose. Once you join the rat-race it is hard to go back to less energy intensive living. There is an argument for not forcing change on tribes who are perfectly happy as they are.

MOBILE SOLAR & WIND POWER - Ideal for villages in Sub-Saharan Africa where electricity is scarce, and tsunami devastated regions in Asia for emergency supplies, units like this can provide stand-by electricity or instant power where none exists at the moment. This is another solution to potential world challenges from the Cleaner Ocean Foundation and Climate Change Trust. The vehicle shown is part of an experiment in connection with river and ocean cleaning vehicles on water.

Providing clean, sustainable, and affordable energy to all is a priority for governments around the world and is one of the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals for 2030. In 2016, 1.1 billion people (14 percent of the global population) were without electricity, and 2.8 billion (37 percent) lacked access to clean fuels. Human development and energy use are intrinsically linked: energy is needed to provide for human needs, such as clean air, health, food and water, education and basic human rights; and it is fundamental to the development of every economic sector.

EUROPEAN UNION

It is estimated that more than 50 million households in the European Union are experiencing energy poverty.

The EU Energy Poverty Observatory (EPOV) is a 40 month project that commenced in December 2016. Its principal mission is to engender transformational change in knowledge about the extent of energy poverty in Europe, and innovative policies and practices to combat it. The creation of an Energy Poverty Observatory is part of the European Commission’s policy efforts to address energy poverty across EU countries. The Observatory aims in particular to:

WIND

POWER - Wind, hydro, and solar can supply more than enough power to achieve universal access to electricity.

Global access to electricity has accelerated over the past two decades, with growing reliance on coal and hydropower. A wide range of electrification options can help eradicate energy poverty, from small devices deployed locally to utility-scale solutions. All renewable energy sources, including hydro, wind, and solar photovoltaics (PV), offer scalable applications in a range of locations and with a variety of grid connections and power-output capacities.

DEFINITION OF ENERGY POVERTY

There are several different approaches to define energy poverty and they can be classified as follows:

SOLAR POWER - Electrification solutions range in scope from small local solutions to mini-grid interconnections and national-grid development. Grid-extension (transmission and distribution lines) or micro-grid systems are the most cost-effective solutions for electrification in areas where demand intensity is high. But considerable upfront investments are generally needed, and operation and maintenance costs might also be high depending on local conditions. For less dense urban areas, remote areas, or complex terrains, other off-grid solutions might be cheaper but will generally provide less reliable power services. Further, electrification can follow various progressive paths—from small local solutions and mini-grids interconnections to national grid development.

THE LONG & SHORT OF IT

In the short term we are reliant on fossil fuels to take us into an age of long term energy security. We can thank energy supply companies for that, for making fuel affordable until such time as they switch to cleaner renewable energy is possible. Those companies may want the think about investing in alternatives.

That switch may have to be sooner than any politician thought previously.

Austria - Croatia - Czech Republic - European Union - France Germany - Ireland - Italy - Japan - Netherlands - Poland Portugal Slovakia - Slovenia - Spain - United Kingdom

LINKS & REFERENCE

http://energy-transition-institute.com/Insights/EnergyPoverty.html https://www.seforall.org/ https://energypedia.info/wiki/Energy_Poverty https://www.energypoverty.eu/relevant-organisations https://www.energypoverty.eu/

Please use our A-Z INDEX to navigate this site

|

|

|

This website is provided on a free basis as a public information service. copyright © Climate Change Trust 2019. Solar Studios, BN271RF, United Kingdom.

|